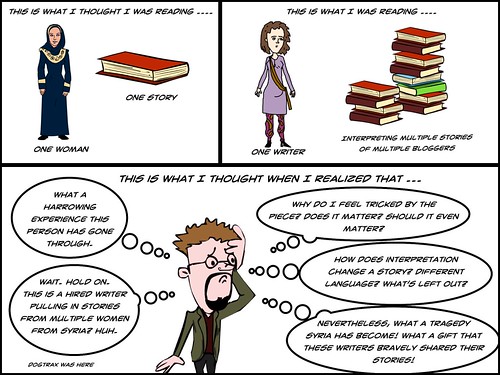

There’s a moment of realization upon reading “War in Translation: Giving Voice to the Women of Syria” by Lina Mounzer when her opening stories of anguish and war and struggle give way to the realization that she is writing in a collective voice. I found myself jolted (although, to be honest, if only I had spent more time reading the title of the piece, perhaps I would have better realized the situation).

I made a note of this surprise in the annotated margins of the article, as folks in Equity Unbound (including Maha’s class in Egypt) are crowd-annotating Mounzer’s powerful piece. I don’t want it to be a criticism of Mounzer’s writing, because it is not. (You can read and annotate, too, if you want. Just follow this link to the piece.)

But it did get me thinking about the role of the single reader experiencing a collective story. In this case, Mounzer is distilling the stories of multiple women in Syria who blogged about living in a state of war, and how it impacted their families, their lives, their futures. Her role was as translator, and also as curator of collective voices. Her intention was to give voice to the struggles of women in Syria, and she succeeds.

So what is my role, the reader removed from the scene, in this story? These are some rough thoughts this morning, before I head back into the text for more reading.

A reader must determine veracity. We live in the age of Fake News and Unreliable News. I did my due diligence by following the biography of Mounzer and her organization, and determined as best as I could that she seemed to be who she says she is, and that I could believe in her work. This is key to a collective story format like this, as a curator and translator could easily invent stories to make a point. The ‘multiple voice’ format is easily manipulated by a writer. That does not appear to be the case here. I believe these stories.

A reader must be willing to be transported. Aleppo is far from my home. I am in a comfortable, and safe, space as I read about these brave women trying to survive under a brutal regime and violent revolution. As reader, I must try to make their stories present in my head and in my heart. I must try to understand. In this case, the act of crowd-annotation is helpful, for it forces the reader to interact with the text on a meaningful level. I can’t ignore the stories. I have to acknowledge them.

A reader should find other readers. This may not be true in all cases — there are plenty of pieces I read alone and never share with anyone — but here, in a piece about collective voices that comes within a theme about avoiding “the single story,” it seems rather important that readers gather together to read together. The use of Hypothesis helps this. The reader is not alone, as the Syrian bloggers are not alone. As Mounzer brings the writers together, so does Hypothesis and Equity Unbound bring readers together.

A reader brings themselves and their own stories into the texts. I am thinking of how engaging with the text from other people from other parts of the world has the potential to expand my own understanding of the world. One’s perspective of Syria from the United States is likely different from the perspectives of someone from the Middle East, I suspect. This is because we have different stories to tell, and different ways to make connections to the story of stories we are reading together. I’m not talking about sharing intimate experiences with the world, with people we don’t really know. But readers bring where they were to where they are, and reading other readers is powerful.

When the reader becomes writer, the writer knows they are being read. Sorry for the tricky phrasing, but I was thinking of how the annotations would be received by Mounzer, and if she would find a way to send those comments forth to the women bloggers she has curated. I can visualize this loop, from stories, to curation, to article, to readers, to annotation, to comments, to stories, to writers. Those bloggers needed an audience. They used writing to make sense of an unpredictable world. A world of sadness and violence. We are their audience. You are their audience. Annotation makes the reader visible.

What do you think? What’s the role of the reader in any text?

Peace (thinking),

Kevin

I looked at your cartoon and saw that you had a similar thought about the writer using first person narrative that mixed her perspectives with those of the women she was introducing via her translations and the article. I posted also a comment in the margins about this.

I appreciate your efforts to do due diligence to verify the credibility of these stories. I’ve been following one Twitter account that is regularly posting photos showing the tragedy in Syria. For a while I was reTweeting and liking. Then I found another writer who was saying that much of this imagery may have been artificially created, to sway Western public opinion.

Not being anywhere close to the situation and knowing who, if anyone, is telling the truth, I’ve become more reserved in how I look at the first account.

Only by finding and following trusted writers, such as I’ve found via #Clmooc, can any of us build a sense of trust in what we are seeing on line. That’s sad.

Thank you, Daniel, for your keen insights and for engaging, always. Appreciated.

Kevin