(This is for Slice of Life, a weekly writing adventure hosted by Two Writing Teachers. But this also dovetails into extending the Making Learning Connected MOOC work into the year beyond summer AND how collaboration is a key element of Digital Writing Month underway this month. Phew. Connections flying all over the place.)

I’ve been interesting in finding ways to bring more of the ethos of Connected Learning that forms the heart of the Making Learning Connected MOOC (CLMOOC) into the world beyond the summer months. Certainly, I try to infuse it in my classroom around choice, and digital writing, and collaboration.

But I have been trying to pay attention to opportunities when I can surface Connected Learning with other teachers, particularly in off-line professional development, where participants may be less likely to have ever heard of Connected Learning or the CLMOOC.

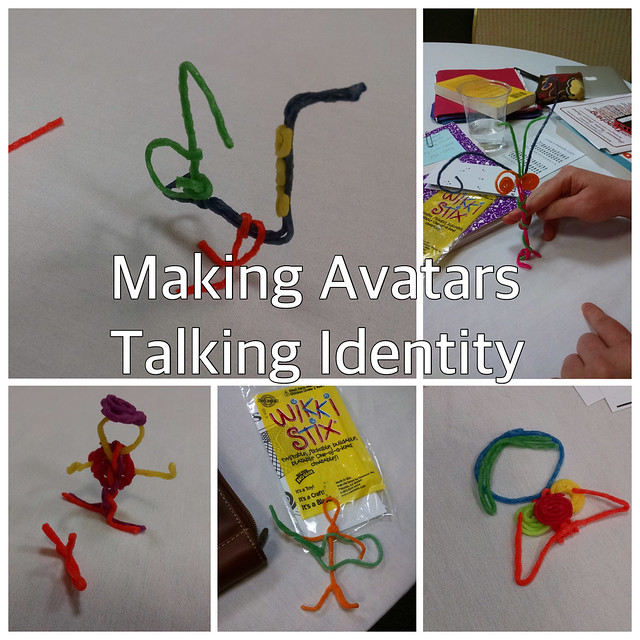

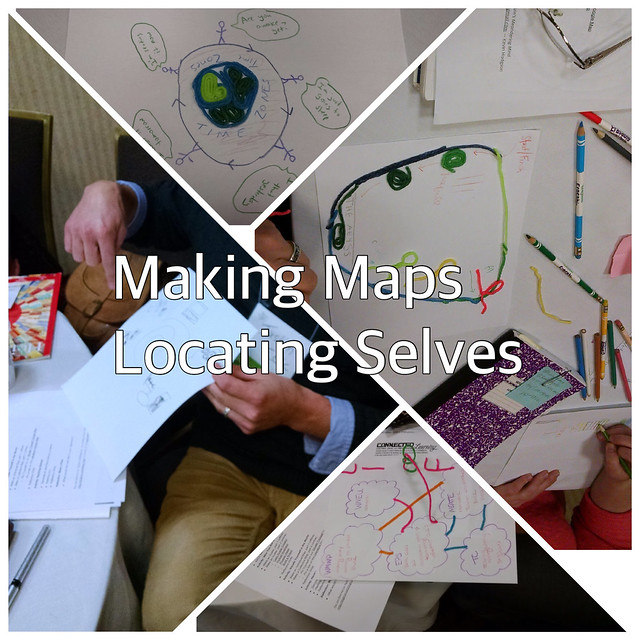

This past weekend, I led a three-hour workshop called Make/Hack/Play (thanks to Bud Hunt for the title of the session .. Bud did his own Make/Hack/Play workshops) for the New England Association of Teachers of English (NEATE) and we dove into hands-on activities in order to talk about what Connected Learning might mean in practice. I was joined by a Western Mass Writing Project colleague, Justin Eck, who is working in a graduate course and designing his own MOOC right now.

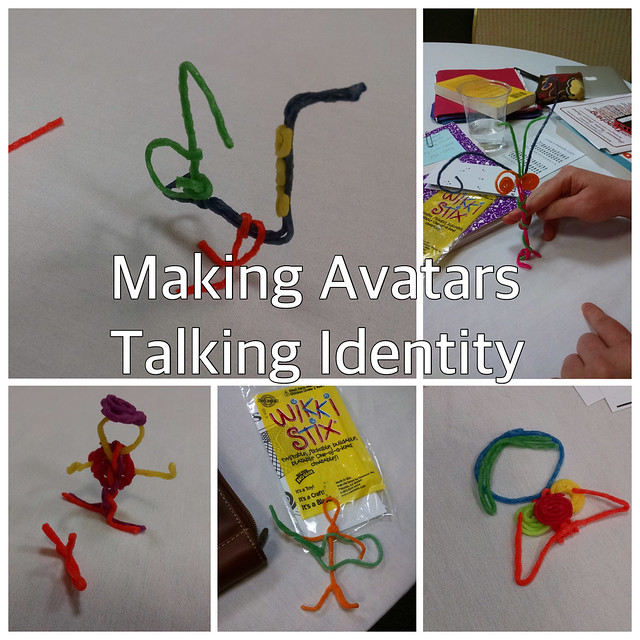

We worked on avatars in order to talk about identity — first, with Wiki Stix at the tables and then in online avatar spaces —

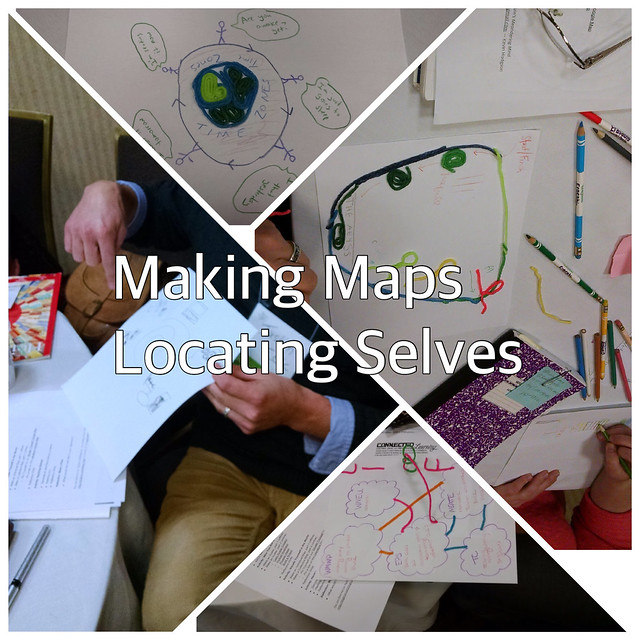

We created conceptual maps in order to symbolically situate ourselves in the world — first, with paper and colored pencils at our seats, and then in online open mapping programs —

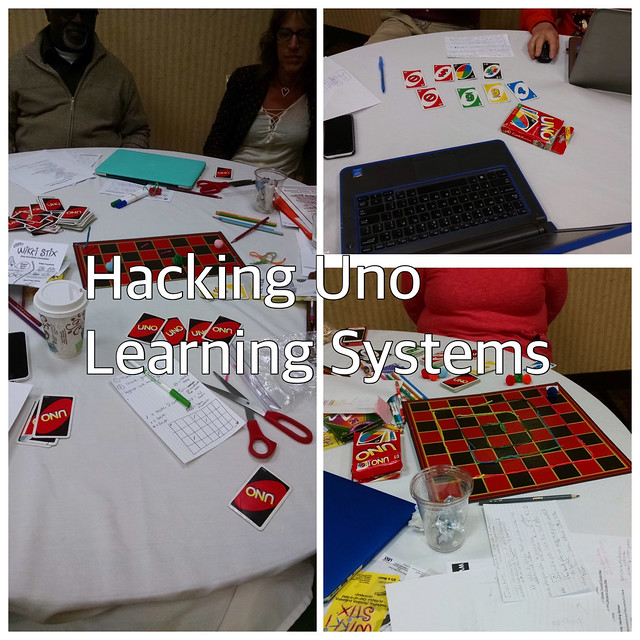

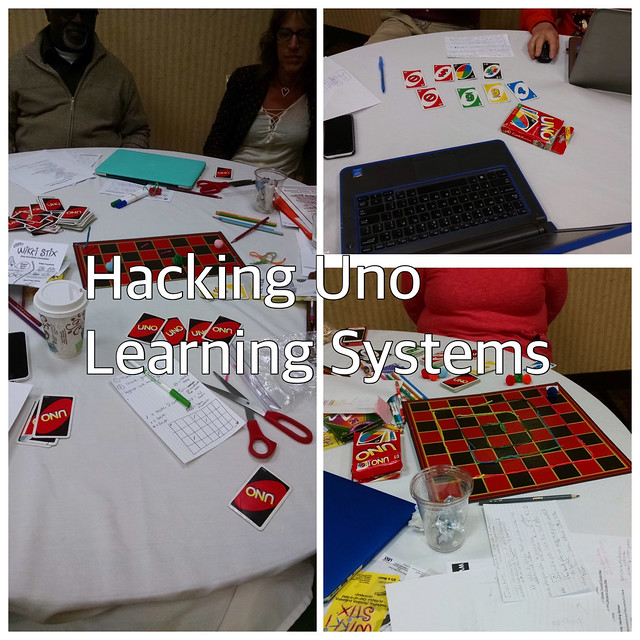

We considered the literacy elements of game design — first, by hacking the game of UNO and then, by sharing out the new rules with others, and then in online, by discussing Gamestar Mechanic as a space for putting game design into practice for an authentic audience —

The activities sparked rich discussions from elementary teachers through university professors, and I believe that the participants came away with a clearer understanding of how Connected Learning taps into the authentic interests of young people and still provides rigorous academic learning, all in a fun and engaging way.

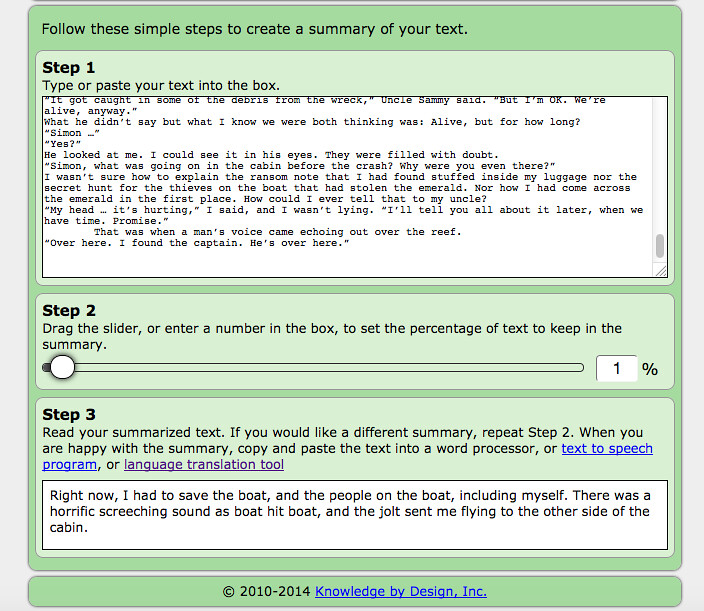

Would you like to collaborate with us? Sure, the session is over but our Literary Landscape map is still wide open. Here’s what we were doing and here’s how you can contribute. The idea is that we are collaboratively creating a map of settings of novels, all tied together on a single map.

First, think of a favorite novel with a distinct setting.

Second, go to the Google Map.

Third, search for the location of the setting in the search bar of the map. Go to that location.

Fourth, click on the “add marker” icon (it looks like a push pin) in the tool bar and drop it onto the map where the novel’s setting is.

Finally, add the title of the book to the text box and use the camera icon to search for an image of the book to attach to your pin.

I look forward to a larger literacy landscape developing … with your help.

Peace (in the collaboration),

Kevin