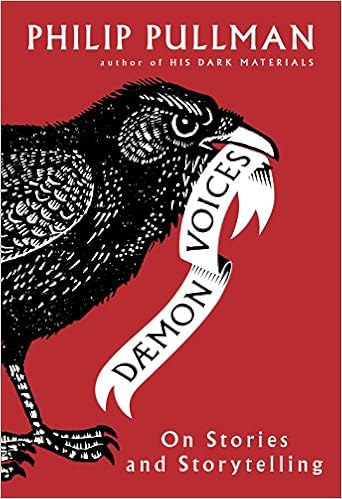

There’s something to be said about stepping into the thinking pages of a talented writer, particularly one who has strong views on the world and yet who also has an open curiosity to the mysteries of stories. This is what you get when you read the essays inside Daemon Voices (On Stories and Storytelling) by Philip Pullman.

Pullman made his name with the His Dark Materials trilogy (which begins with The Golden Compass), is rich with allegory and fantasy, and his most recent fiction trilogy — The Book of Dust — pushes the story even further (with great success, I would argue). He writes with a quick pace of story and with an understanding of how to build an imaginative world that makes sense for that story to be told and for characters to be challenged within that world. These tension points are what drive Pullman’s tales.

Daemon Voices (On Stories and Storytelling) collected a series of lectures and writings he has done over the years about the art of writing. While some of it felt a bit too erudite for my tastes (and his debates about religion didn’t do much for me, so I power-read a few of the later chapters), his explorations of stories and characters, and themes, is quite intriguing, and his defense of children’s books as a legitimate art form with depth and artistry is worth a read alone. As a former teacher, Pullman understands what short thrift children’s stories often get, and argues that the field of criticism and publishing does not do it justice. Readers become writers, and readers become thinkers, Pullman notes.

I always enjoy crawling into the mind of a writer, to see what they see of the world. Of course, this experience is limited (we only see what he wants us to see), yet Pullman’s exploration of where his stories emerge from — mostly, unformed when he begins, and he finds the themes as he moves along into the story — and the way he remains open to inspiration as he writes is worth noting for anyone who writes.

Pullman is an intellectual guide into the art of the imagination.

Peace (dreaming of daemons and bears),

Kevin