Here is a collection of podcasted Video Game Reviews by my students:

Peace (in the game),

Kevin

Here is a screenshot/video capture look at some of the science-based video games my students are creating, along the science-based theme of cells. You can see a bit about how they are using text and story to frame their game within a science and narrative context. The project weaves game design, science and narrative story together, and many students are now either done or finishing up.

Peace (in the cell),

Kevin

As I was reading and assessing video game reviews by my students, I created a list of the games they chose to write about. Here is a Word Cloud of the most popular of the video games in the mix for my young writers:

You’ll see that Minecraft is there, front and center. No surprise. But Trivia Crack? Lots of girls are playing the app, apparently, and if the reviews are right, it is a social game of sorts with trivia. Never heard of it. There are some games that make this list year after year, and others that come out of nowhere, depending on culture and games introducing during the year. Crossy Road … another one I had not heard of, but apparently it is a variation on Frogger.

While the game review does not have to be a video game, only one of my students chose a board game this year. All others were video games on assorted platforms.

Here is a review podcast of a student reviewing Metroid Blast:

Peace (in the game),

Kevin

As a companion to our game design unit, my students also write (and many podcast out) persuasive game reviews. The lesson is to integrate writing into our understanding of game design and writing with authority on a topic. Plus, I get a better sense of what games my students are playing year to year (It’s not easy to keep up).

Here is a review of The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess

Peace (in the voice),

Kevin

One of my students has published her video game that we have been working on as a collaboration between my ELA classroom and the science classroom. The topic of the game is cells, and you can tell that the mentor texts we used (Magic School Bus) had a big influence on Sara, who has emerged as one of the top video game designers in the sixth grade.

Peace (in the cell),

Kevin

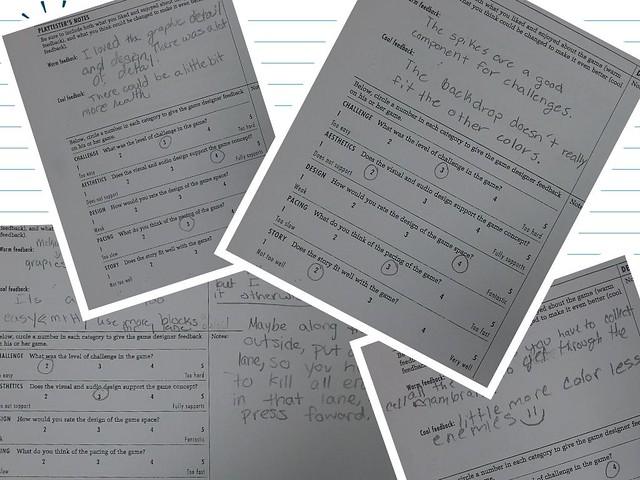

In designing games, as in writing, a valuable step to the process is to gather feedback from someone outside of your own head. During our science-based video game design unit, we play-test each other’s games, and work on giving feedback to what is noticed. While this happens quite a bit informally (“Hey, anyone want to try my game?” – a pretty common refrain in my classroom these days), I do try to formalize it a bit. The form we use comes from a new book on systems thinking, but I also had a similar form that I had made on my own.

I like how this new form incorporates the warm/cool feedback concept, and allows for reaction notes from the game designer. Obviously, this activity began with a mini-lesson on giving constructive feedback to other game designers, and how to use warm/cool feedback on someone else’s work.

It’s still interesting how some students read and accept the feedback, and ask for clarification from the play-testers, making adjustments to their projects, while others just shrug and go on as if the process never happened. They can’t get out of their own heads, and see the game objectively (“Well, I BEAT that level. You should, too. It’s easy.” — a student said this to me the other day. Me: “Well, you BUILT that level, so you know it inside and out. It’s not easy at all if you don’t know it.”). This is part of the learning process.

Peace (in the game),

Kevin

One of the things I force my students to pay attention to (some resist) is the concept of storyboarding out their science-based video game projects. But I know, from experience, how important it is to have a map forward, even if you abandon the map along the way for more creative terrain.

As a teacher, the storyboard also provides me with a way to see what they are thinking as they begin the design phase, as well as gives us discussion points on which to talk through the game design, science concepts and story ideas in a workshop-style mode.

You can read more about what I wrote about storyboarding, including the sharing of resources, over at the Gamestar Mechanic teacher site, from a few years ago.

Peace (in the boards),

Kevin

Moving into a unit about video game design also means talking about how to tell a story in ways different than a short story or traditional narrative. I talk to my students about how they should see their science-based video game as a story that the reader will play. They should be entertained, and challenged, and also educated about cells (the science topic that is the centerpiece of the video game design project)

I’ve come to call this the “storyframe” of the video game (rhyming is helpful technique). The story is the narrative wrapper in which the game play itself is situated.

Of all the elements of our game design, this is one of the trickiest for my students. First of all, there are the confines of Gamestar Mechanic, which allows text in the title of the start of the game and at every level, but not a whole lot of room. Students can earn message blocks, which are handy, and they can earn some sprites that “talk” (via text messages).

What must occur is the use of metaphor (this represents that), focused narrative text that moves the player/reader along on their journey through the game system, and a sense of flow. That’s a lot to ask for from a sixth grader, but they can do it. It does require me to be conferencing a lot, reminding them of what good games do (and how to make a game better), and feedback from peers during the initial stages of design.

You know what the best resource is for this discussion around storyframes? The Magic School Bus series. No one did it better, particularly when we talk about science and storytelling. And, what franchise effectively jumped across mediums so well? From picture books to television show to video games, The Magic School Bus showed how transmedia can work.

Building that kind of story? Well, that’s what my students are in the midst in right now.

Peace (in the construction of story),

Kevin

(This is part of Slice of Life, a weekly writing feature hosted via Two Writing Teachers. Narrow your lens. Write. Share.)

You’d think with all the video game design work I do with my students that I would have already been kneedeep into Minecraft. My students certainly are. Me? Not much. No real reason except time to dive in always slips away from me, but now that my youngest son is using and loving Minecraft (and even joined a Minecraft club at our public library), I figured it was time to dip my toes into the blocks, so to speak.

So, I asked my son, teach me Minecraft.

And we proceeded to spend about 45 minutes with the Minecraft App (we also have the fuller version on the laptop), and together, he helped me build a doghouse for the dog/wolf that we spawned in the world that I began to create when we started to play in Creative — not Survival — mode. (Getting the vocabulary down …) I had to remind him to talk me through the learning, not do it himself. (such a teacher)

OK, so now I get a bit of the appeal of Minecraft. I was never quite oblivious to it but I can see how the building and wandering in the world is a pretty fascinating experience. I spent some time “flying” high above the world, watching the contours being drawn out in each direction. That was pretty nifty, to think we were in the map as it was being made.

And the dogs seemed pretty happy.

Peace (in the craft),

Kevin