These come from the annotation activity of an article called New Media Art, a chapter from a collection published in 2006. In Networked Narratives, one of the activities this week is to annotate the article and examine the nature of New Media Art (or whatever title it has these days.)

I was intrigued by some of the early examples of video games as the source for art, and found two examples referenced in the writing that still live on the Internet. Notice how each artists used elements from the game, but remixed and remediated them in such a way to create something new and inventive.

Pretty interesting ….

The first video example of Game Art is The Intruder (although this is only a video capture since the original experience no longer exists with modern browsers, as far as I can tell)

From a description of the original experience, via BookChin

In Natalie Bookchin’s piece, The Intruder, we are presented with a sequence of ten videog ames, most of which are adapted from classics such as Pong and Space Invaders. We interact via moving or clicking the mouse, and by making whatever we make of/with/from the story. Meaning is always constructed, never on a plate. The interaction is less focused on video game play than it is on advancing the narrative of the story we hear throughout the presentation of the ten games.

The Intruder – Natalie Bookchin (1998 – 1999) from jonCates on Vimeo.

The second example is Velvet Strike

From its description:

Velvet Strike was a set of counter-military graffiti sprays for a spray-gun modification in the networked game Counter-Strike. Players could both download and spray images from the collection in-game and also create and contribute new spray paint graphics to the intervention. The project was created in response to the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and specifically the proliferation of militaristic anti-Arab, anti-Muslim Counter-Strike modifications following 9-11. Velvet Strike faced a massive backlash from gamers (particularly in the form of misogynist verbal attacks directed at Schleiner), raising important questions surrounding the uncritical acceptance of violent military fantasy in games and the role of networked multiplayer games as public space.

And then there is something simple, and yet beautiful, about something like this: taking video of the clouds in Super Mario and making the clouds into their own video. That’s what Cory Arcangel did in 2002.

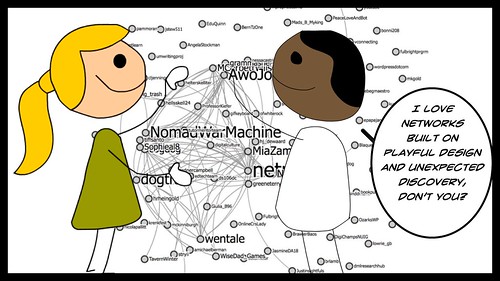

In the NetNarr Twitter stream, one of the students shared a blog post with images of cities he built within a gaming city itself, and I decided to do a little remix. Using game worlds as the setting for Media Art is intriguing.

Your imagined game city, in motion. A #netnarr remix (with apologies) pic.twitter.com/ddGGOb3T2l

— KevinHodgson (@dogtrax) January 26, 2018

What I wonder about is this: are there communities out there doing this kind of work of appropriating video games into art still today, in 2018, and how might I learn more about how to teach my sixth graders — who are now video game designers — to do something similar with their own video games designed and published this school year?

Hmmm.

Peace (game on, into story),

Kevin

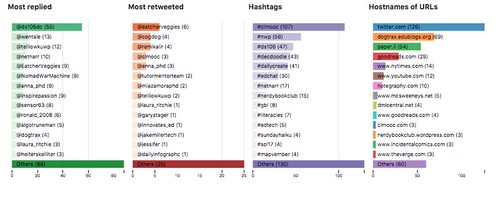

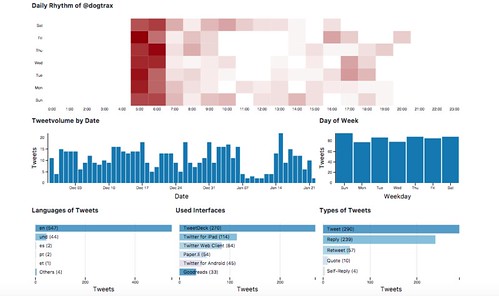

You can see the time period earlier this month where I took a step back from Twitter — and

You can see the time period earlier this month where I took a step back from Twitter — and