Today, I am off to the University of Massachusetts to co-facilitate the first of three sessions around using the Library of Congress digital archives for primary sources for inquiry projects. This professional development course is a collaboration between our Western Massachusetts Writing Project and a local educational collaborative that does a lot of professional development.

Our aim is to help teachers construct “text sets” of primary sources and develop questions and tasks that spark student inquiry and open-ended explorations.

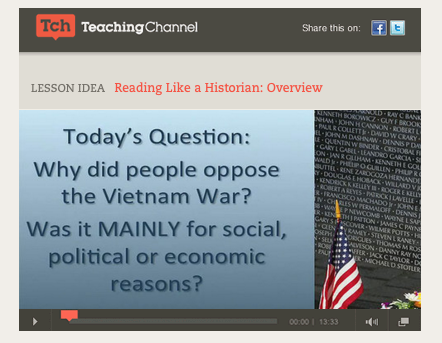

I was reminded of this great video from Teaching Channel called Reading Like a Historian and figured it was worth sharing out. It shows a classroom where the focus is on reading archives and primary sources through the lens of a critical historian. I hope we have time to share it during our session today … (the embed is strange here, so you might be better served going to the source)

Peace (in the think),

Kevin