Last summer, as part of our summer camp at the Springfield Armory National Historic Site, we were exploring themes of immigration, and its impact on our region of Western Massachusetts.

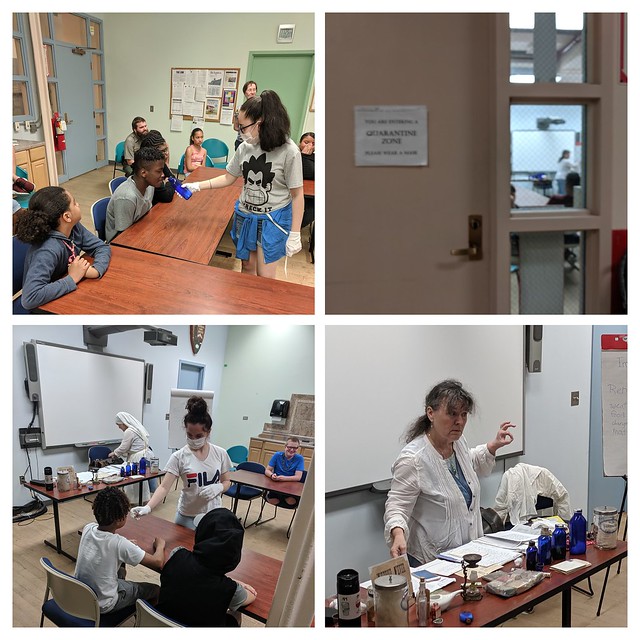

We invited a historic re-enactor to come for an afternoon (we’ve had her as a guest before and she is great) to give a presentation about the Flu Pandemic of 1918, as immigrants were often blamed for the transmission of the virus into the United States (even though all evidence supports that US soldiers in World War I brought the flu to Europe and beyond).

It was an immersive presentation (see my post about the day at camp), with things to smell, things to touch, maps to read and the story of the world grappling with a pandemic that killed millions and forever effected many communities around the world. It was that bad.

So when I read about Fever Year: The Killer Flu of 1918 by Don Brown, I saw the connection and took it out of the library. The book is wonderful, and difficult to take in — the scale of the tragedy is difficult to wrap one’s head around, particularly as the medical world not only didn’t know what was causing people to die and get sick, but also, that the world was not ready for the scale of death and sickness. This was both because the war was still raging and also because the medical field had not advanced enough to make sense of what was happening.

Brown effectively uses the graphic novel approach to tell the story of the Flu, but also of the people battling it — with nurses coming out as the main heroes of the tale. The nurses — and those who were quickly recruited to come nurses, as the war had drawn many from hospitals and clinics — went into communities, worked long hours and longer days, took care of the elderly and the very sick, sacrificed their own lives to support others.

Fever Dream has its lens wide – the world — and narrow — neighborhoods, and in doing so, Brown has successfully captured the scope of a pandemic, and reminded us that we always need to be on the lookout for the next one.

This book might be a little too intense for elementary students, and maybe even some middle school students. But high school students might use it for connection to understanding the modern global, connected world — both as a good thing (share ideas) and a dangerous thing (share disease).

Peace (and health),

Kevin