I’m about halfway through grading an adventure short story project, which means at this point I have read through about 40 short stories from sixth graders. I’ve been pretty impressed so far with the writing as many of the stories have improved drastically from the brainstorming sessions, the peer review activities and the rough draft stages that they went through to get to a final story they could be proud of.

We focused a lot on character development, points of action to move the plot forward, conflict and resolution, and establishment of setting to inform a story. They have a rubric to guide them, and we look at examplars of adventure stories.

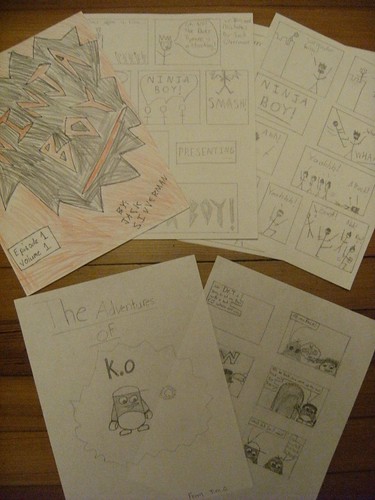

This is the first year I had students (two boys) ask if they could create a graphic story instead of a textual story. Now, I have graphic novels all over the room, and we use a webcomic site pretty regularly, and it seemed wrong for me to tell these young writers, no, graphic novels won’t be allowed for you as writers. Plus, I was interested in what they would. I did warn them, though, that the same rubric and standards should guide them as well as everyone else. I wanted them to know a simple comic strip would not hold muster for this project.

One student was more successful at the creation of an adventure graphic story than the other was, but I was impressed with both. Even the weaker of the stories showed character development in ways that might not have happened in a short story (this student is a struggling writer) and the graphic story opportunity gave him another way to write. It was clear that he used a character that he had already “developed” and was probably using in stories written at home, on his own. I wanted to validate that kind of writing in the classroom, too.

Other things that are jumping out at me right now with the stories I have read:

- Some students get the idea of a “kicker” or twist at the end of a short story. This requires real critical thinking skills, and not all sixth graders are there yet. One story — The Homework Machine — is about a group of kids trying to steal this Homework Machine, only to find out at the very end that it GIVES homework, not DOES homework. That was a nice Twilight Zone twist.

- Technology has crept into many of the stories. One story is all about a brainiac young kid nicknamed Intel, who uses his ability to fix things and make things for this spy story. There are some vivid descriptions of cool tech toys, like a version of James Bond for kids.

- A couple of students have attempted stories that include time shifts — pushing the reader back and forth in time as the narrative slowly unfolds. This is not easy to do and doesn’t always work. But just planning that kind of story out requires deep thinking. What foreshadowing do you use?

- A few stories move from one narrator to another, bouncing back and forth between what we assume are the protagonist and the antagonist, only to discover that our assumptions are wrong. Again, it’s hard to pull this off. One story, about a spy looking for a gadget that turns out to be a mechanical spider which can clone itself, unfolded perfectly, so we felt sympathy for what we think is the antagonist, and then the story turns itself around.

Some trends that I am seeing that I need to work on with them:

- In some stories, the narrative point of view suddenly shifts. For example, the writer sets up a character that we see in Third Person and then midway through the story, the words “I” and “we” are inserted and now we are in First Person. I suspect this comes from starting a story one day and then working on it another day.

- The formatting of dialogue continues to be a struggle for some students. We worked on this a lot in class — with writing prompts, reading examples and looking to novels. I pushed hard because I know they have not been taught this much in the past, and their urge is to write a short story as OneSingleParagraph.

- Resolving a story is so much more difficult than setting a story into motion. Even with graphic organizers and work on plotting out the plot, you can tell just by reading which students got lost halfway through their story and struggled with how to end it. Even us adults have this problem — an idea sparks, flow and then sputters.

I’m off to read another 40 stories.

Peace (in the reflections of assessment),

Kevin