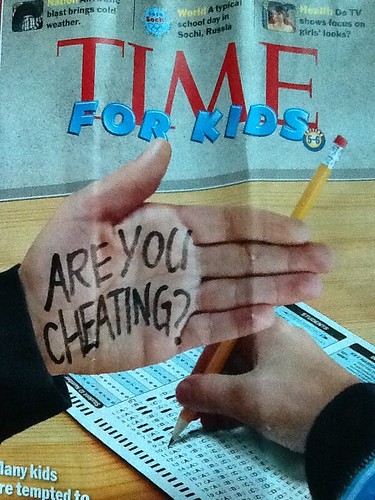

Classroom Cheating

Over in the #rhizo14 learning space, the topic for the first week is all about “cheating as learning,” which is a fascinating way to get started with an inquiry conversation. Imagine my surprise when, as I was spending a few days mulling over this concept, this issue of Time for Kids comes to my classroom during the week. It’s all about cheating in school.

Is that strange or what?

Now, as far as I know (and really, we don’t really know unless someone is caught), not too many of my sixth graders cheat on test and projects. But the article opened up an interesting conversation with my students about why kids would cheat (not them, of course — ahem). They articulated worries about grades, and expectations of teachers, and the need to prove themselves and keep up with friends. Even at this young age, they carry a lot of weight on their shoulders most of the time.

An interesting element of the article centered on the the areas between “cheating” and “collaboration.” Check out this great quote from the Time for Kids article:

“Teachers assume it’s independent work unless they tell you otherwise. But students assume it’s collaborative work unless you are told it is not.” — Tricia Bertram Gallant, co-author of Cheating in School: What We Know and What We Can Do.

That was a real eye-opener for me … because I think it is true. Students are natural social collaborators (look at how they flock to social networking sites) and during work times, they naturally gravitate towards each other. Am I always crystal clear on what is acceptable for collaboration and what is not? I think so, but maybe not. It’s a matter of perception and point of view, and perhaps one person’s view of “cheating” is not everyone’s point of view.

Video Games and Cheat Codes

We’re also wrapping up our science-based video game design unit, and what I find so interesting is that “cheat codes” is part of the DNA of gamers and gaming communities. I have a few students who walk around with magazines about how to hack Nintendo games to find Easter Eggs, gain access to hidden levels, and more. Just Google “cheat codes,” and you are bound to come up with a wide array of responses.

Gamers don’t see this kind of cheating as negative. They see it as sharing expertise, and helping others who get “stuck” in a game to succeed. But if this were the classroom, and one student was “stuck” on a test, it would not be acceptable practice for another student to hand out “cheat codes” for the test, right? Of course not. We see this a lot with our work on our gaming site (Gamestar Mechanic) where you have to make your way through a series of Quests in order to gain experience with game design and earn publishing rights. Many students turn to classmates for advice, help and even beating levels for them. This is acceptable practice for both sides: the giver of experience and the receiver of help. But you can see where the dichotomy of ‘the world inside school’ and ‘the world outside of school’ are often in conflict for students.

Faking It on Facebook

Finally, I am in the midst of reading a fascinating book. Fakebook (subtitle: A True Story. Based on Actual Lies) by Dave Cicirelli is all about the author deciding to play a trick on friends by creating a fictional story of his life and sharing his experiences on Facebook. In this fictional life, Cicirelli quits his job and hikes west, gets in trouble the Amish and who knows what else (I am about a third of the way in).

Cicirelli’s observations of creating this fake world that real people believe is happening (it’s on Facebook; it must be true) are very poignant, as he mulls over when does this kind of cheating of other people’s beliefs in him go too far and what does it say of him, the writer, as he creates this real-time social-networking digital story. It’s a fascinating experiment that he undertakes, using trust of friends and families as a storytelling device (and being dishonest about it.)

Peace (in that gray area of life),

Kevin