Yes, my blog title was designed to be provocative. Thanks for following it here.

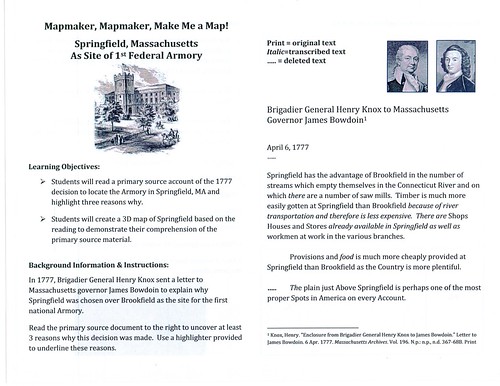

I am a few years into a partnership between the Western Massachusetts Writing Project/National Writing Project and the Springfield Armory National Historic Site/National Park Service, and this topic of guns is often on my mind. The Armory, after all, as one of two main arsenals of our United States government for decades (the other was in Harper’s Ferry), is all about guns and weapons of war, and we use the Armory Museum itself as our classroom for summer camps (one just ended) and professional development courses for teachers (another one is planned for the fall.)

Reconciling the use of a building housing devices of violence with the rich history and the amazing primary sources it provides as windows on the past is one I still grapple with, although I continue to find the partnership to be fruitful and collaborative and informative at all levels. Still … guns. They’re everywhere in our learning spaces.

Here’s what we have done to try to balance or mitigate these two often conflicting ideas when we have worked with middle and high school students at our summer camp we run at the Armory itself (and also, some of these are how we work with teachers to use local history in their classrooms):

- We focus on the engineering design and innovation of manufacturing. We don’t ignore that what was being built here at the Springfield Armory was designed for war. But we pivot to the ways that innovations at the Armory transformed our Pioneer Valley, and the entire country, as the Armory’s work influenced other elements of the United States government operations.

- We focus on the workers — from explorations of how immigration patterns during WW2 helped the Armory expand its workforce to meet the demands of war; to the role that women played when men went off to war, and the generational impact that had in the years following the wars; to the racial divisions that often played out at the Armory as a microcosm of the United States itself.

- We use the stories behind the weapons — either from the manufacturing side or from some of the guns on display that have been personalized by the user, with engravings of tales and years and battles, and humanize the soldier on the battlefield, not glorify the guns they held. The object as holder of stories is a powerful instrument of learning.

- A deep look at Shays Rebellion — when farmers and former soldiers of the Revolutionary War rose up in protest over taxes and marched to the Springfield Armory with a plan to take the guns — allows us to make connections to the present ideas of community protest, and the fuzzy line between right and wrong, and acceptable and unacceptable use of force, and the role of the federal and state government in the lives of its citizens.

- We use creative writing to push the idea of guns in the museum in other directions. For example, one prompt was to design a “gun for good” by creating a patent design, with labels and explanations, for a gun-delivery-system for something positive. Campers designed guns that sent forth ice cream, money, technology, music and, my favorite, new homes for the homeless of Springfield. Another prompt had them designing their own museums, using the Armory as a mentor text. And yet another was to design a board game about the Armory, with history as the springboard for play.

Four years into my partnership with the Armory (which began two years before I even came into the mix with other WMWP colleagues), and I still feel a bit unsettled by the weapons part of the museum. It’s an entire wing of weapons, including grenade launchers and machine guns and other advanced killing technology. Cases and cases of them, all tied to history, of course.

Even as a former soldier (infantry sergeant, National Guard) who was once trained on many of the modern weapons in the cases, I always encounter my own internal resistance to bringing young people in there. I am strongly in favor of gun control legislation and abhor the political work of the NRA to influence politicians to thwart any kind of reasonable measures to protect lives from guns.

Hopefully, by finding other ways to connect to the history of the Armory, we bring the importance of the building and the site to the surface for city kids who might not otherwise be aware. For some, the guns are what brings them to camp. This is the reality. Our job is to the show the toll of guns, and the role they played in America’s wars, but also to use them to tell the stories of the people behind them.

Peace (I mean it),

Kevin