You can’t be around kids at any age for any amount of time and not worry about what the extended use of small and large screens is doing to the developmental brain. But it still feels so anecdotal. Our teacher lunch room is full of stories and complaints about diminishing attention spans, student writing primarily centered on video games, lack of persistence, and more.

As someone interested in the possibilities of digital literacies, as well as a father, this shifts that seems to be moving under our feet as we move into a more digital world is unsettling, too. It feels as if we are in one of those epoch moments – like moving from oral to written stories, or the age of Gutenberg — where we don’t really know what will emerge from the digital revolution, and we’re hoping for good things but fear the bad.

Reader, Come Home (The Reading Brain in a Digital World) by Maryanne Wolf is the perfect read for this unsettled moment. It will not, by any stretch, ease your mind. In fact, Wolf, a reading teacher and brain specialist who has worked for years on reading skills, will likely set off alarms, if anyone is listening.

And if you’re not listening, you should be.

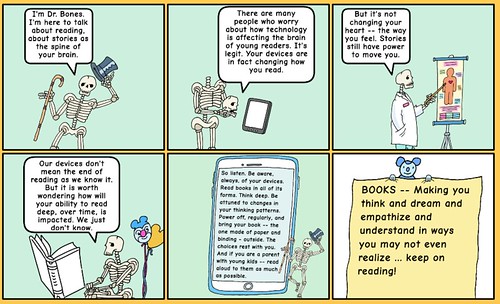

Wolf’s main premise, supported through multiple findings from emerging research, is that reading on the screen, particularly for young children, is fundamentally changing the way the brain works with the processing information, and that the drastic decline of book reading – the paper bound things on the shelves — in favor of device reading is altering the complicated way the brain develops, over time, to be able to not just process information, deeply, but also to spur comprehension and connections beyond the textural levels.

Wolf would say that my sentence in that last paragraph is too long for a screen-developed reader to read and understand, and she pulls in research showing this to be true. And she explores her own reading life, too, to show how even she (and maybe you, and certainly me) have had our reading lives changed and altered by our time with screens.

Wolf, for example, does a scientific experiment on her own reading of a Herman Hess novel she loved and found she could not attend to the book for even moderate stretches of time. Her thinking would not follow Hess’s complex sentences and ideas. However, she was able to retrain herself back to deeper reading, which informs her ideas about how to address screen reading.

I won’t share all of her scientific explanations, except to say that when a young child is learning to read, each story and each book is part of the layered growth of the brain, building on the previous. Each book is layered on the last. Each story becomes a connector point for the next.

When a young child reads on a screen, though, the pleasure motivator of entertainment — the media, the links, the ancillary information — not only encourages them to skim the surface of text, but teaches them that this is how you read text. The brain remembers and builds those skills with multiple reading. When the brain encounters text, any text, those — skimming, searching for entertainment — are the skills it draws upon.

Research has shown that depth of understanding and retention is definitely impacted by screen reading. And, worse, skills that one might develop by reading with a screen do not transfer over to the skills needed for traditional reading on paper. If anything, the screen reading skills diminish the paper reading skills. This is the counter to the argument that people are doing more reading than every these days, just in smaller segments on smaller screens. Reading on screens is not reading in books.

The implications of that are what we are seeing in our classrooms and complaining about in our teacher rooms. It’s what so many of us parents fret about when we don’t see our children reading for any extended periods of time anymore. It’s a generational shift. And it may not bode well for the future.

Wolf explains that families have many reasons for handing over a device to a young reader — it becomes the babysitter for harried parents, it might be viewed by immigrant families as a better teacher of language, it starts as a minor entertainment diversion and escalates into something larger in the lives of children, etc.

Wolf does not advocate a “head in the sand” philosophy nor a complete shut-down of all screen reading. Instead, she suggests a path forward, acknowledging the likelihood that devices and screens will continue to dominate the lives of young people (and she does tackle some digital access issues and socio-economic disparities in our communities).

Her central suggestion to addressing the problem of screen readers is to first educate more parents and families on the benefits of “read aloud” between small child and adult — the benefits are many and complex, and all research indicates that reading aloud to infants through teenagers (good luck) has immeasurable impacts on academic performance and success in later years. She notes how many pediatric offices now provide books for all families visiting for check-ups, and use the interaction in the doctor office to teach about the importance of reading aloud.

But Wolf also suggests that our educational system needs to make a significant shift in how we approach the teaching of emerging readers. She lays out three tiers of her approach — but the main element is that we explicitly teach both reading of books and reading of screens in the early elementary years (each requires different reading skills.) By teaching skills in how/when to read digital texts and also how/when to read traditional texts, a young reader begins to develop what Wolf calls “a Biliterate Brain,” trained to understand that we read on the screen in one way for a specific reason while we read books in another way for another reason.

Her hypothesis — based on her work in childhood brain research — is that eventually, the adolescent brain will merge those two skills into a solidified reading approach and will instantly toggle between skills needed for a certain kind of text — reading as code-switching on auto-pilot.

This would require pretty significant shifts in how we teach literacy in school, of course. While many classrooms have devices or computers or access to mobile phones, the curriculum around explicit teaching of reading digitally for comprehension is not a significant part of the educational landscape. It should be.

Even Wolf doesn’t claim to know if this approach of “biliteracy” will work, but she argues that we can’t just sit by and watch a generation of young readers learn to read on screens. The altering of our brains from our devices is real. So is the altering of the brains of our children, and our students, and our future. It’s not enough to shrug our shoulders and hand another device into small hands. We need to recognize the issue and begin to something about it.

It’s up to all of us.

Peace (on paper),

Kevin