If you read the provocative title of this post and thought, what rant is he on now, you’ll be disappointed. Go on. It’s OK. You can move on other blogs, if you want. Or stay. Please do. I’m happy to have you here. It’s the end of the Rhizomatic Learning course (wrong word for what it is/was) at P2PU and this week, facilitator Dave Cormier has us thinking about how we move off center stage and allow for learning to become the natural fabric of our lives, without structured support.

How do we plan for “planned obsolescence” when we are the teacher or when we are the learner in a specific learning space?

If, like me, you are a classroom educator, this is more of a June discussion (in New England, anyway) with summer approaching, not a February think when winter is still in full gear. Here, in February, I am still center stage with my sixth graders, guiding them as best as I can towards ways to think and write about their world. I hope something catches. In June, as the year winds down, I will be more contemplative — wondering, Did anything catch? Anything at all? Will they still remember our lens of thinking five, ten, 15 years down the road? Did I do what I set out to do?

It’s difficult to have a rhizomatic thinking pattern when you in the midst of the learning. If these discussions have taught me anything, it is that simple fact. We have trouble making sense of the moments when we are in the moments. I suspect it takes a reflective stance and a larger-picture understanding of our place in the world to gain insights about what we have truly, deeply learned. Time forges on. Yet, learning experiences can also begin to fade, if we are not careful. We must have a forced-memory strategy, as a way to call back the experiences. I use writing. Words to remember. This blog space works in that vein. I am collecting ideas and reactions and reflections in this moment in hopes that later, I will come back and better understand what it is I was doing. I will. I do.

Because right now, right here, as #rhizo14 ends — I don’t know what I have learned. Not yet, anyway.

I began the #rhizo14 with a poem (see Zeega, above), about roots taking hold. Those roots? Still taking hold for me. Still. May those roots of new ideas keep working their way into my head, and keep finding new ways to transform the way I see the world so that, perhaps, some of that transformation seeps its way into my teaching, so that I may help transform the thinking of my students, whom may not even know it until years later. Roots often remain hidden until we suddenly realize they are in full bloom.

It occurs to me as I write this post that some of the same ideas are also being explored, although slightly differently, in the Deeper Learning MOOC, too. There, we’re talking about to how create rich and meaningful learning opportunities, spaces and connections for students so that it just not a shallow scrape of the surface of ideas. Deep resonated with all of us — as teachers designing those possibilities in hopes that something will catch in the mind of kids and as learners trying to make better sense of the world and ourselves.

What it takes to reach that point of rich learning is some faith on the part of the learner. Hope that our experiences matter. That we’ve gathered something important from our time spent together. That the shared journey holds us together. Roots take hold.

Peace (in some final thoughts),

Kevin

PS — here are two comments I left in the P2PU site that align to some of the thinking:

We banter about the term “lifelong learners” in education quite a bit. It’s a hopeful sentiment — that the learning opportunities in our space will not just spill over in the lives of our students (I teach 11 year olds) but will provide the structure for self-centered learning in unknown situations at any given time in the future. In some ways, the younger the students, the more difficult this is because of the ways that technology and digital media are completely transforming the world (Remember the world of 10 years past?).

We have no idea what the world of work and life will be like for my sixth graders when they graduate high school in six years or college in 10 years (more or less). To think otherwise would be foolish. But such conundrums open doors, too, if we don our optimistic lens. We have to be mindful of thinking practices that transcend the moment.

Same here, with this course and others in open education. I can’t even articulate what I will take away from #rhizo14 because I may not even know I learned it until the moment I need it .. and remember. But I suspect seeds have been planted. I am optimistic that my time spent here, with everyone in conversation and creation, will be fruitful in ways I don’t yet know. In the unknowing is the hint of knowledge, right?

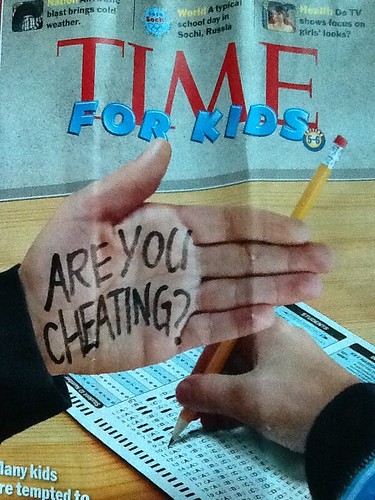

But you can see how that thinking would drive educational policy wonks crazy. There are no fixed data points on that kind of learning. You can’t test me on what I have learned in #rhizo14. Well, you can, but I’d cheat on that test. (Take that data point, you wonk!)

and

I just started to read danah boy’s new book, It’s Complicated (the social lives of networked teens), and one of her themes is that teens have now become so connected and so part of the social web fabric (even if they are not always sure what they are doing) partly due to of us parents and teachers (yes, the very ones who fret over so much screen time and online interactions). We are the ones who have micromanaged their days, and hours, and interactions. We are the ones who see free time as wasted time. The teens she interviews in her book express frustration that there is no time to just hang out in real space, so they turn to online spaces to do what they don’t have time to do otherwise. This observation connects to the theme here this week for me because we (my teaching colleagues and I) have noticed more and more students not being able to independently persevere when confronted with a problem with no easy answer. They give up before they start. They immediately seek adult guidance. They have little confidence that they can learn it by doing it. They don’t trust themselves. So, this question of enduring learning is something my colleagues and I talk about, and talk to our students about. And chat with parents about, delicately. It’s fascinatingly frustrating. (and boyd’s book is a must-read)