I will never to be accused to being a “gamer,” which is not to say that I don’t appreciate the world of video gaming. I spent many (perhaps too many) hours of my childhood and teen age years, playing Atari and Nintendo and other game systems that I was pretty decent at. I kicked butt at Pong, and was a master at Donkey Kong, and I could discover many hidden Easter Eggs in other platform games whose names have since escaped me (Legend of Zelda seems to be one that stays with me).

These days, though, I mostly watch from afar as my own boys play on the Wii or their iPod Touch or on the computer. We limit their time in the gaming world and put the brakes on some games that we deem inappropriate, but still, it is fascinating to see how far gaming has come and to wonder about where it is heading, and to consider what value gaming might have in the classroom.

I am in the midst of writing an article about gaming in the classroom, with the emphasis on how it might be used for learning. Critical thinking, collaboration, design principles and more are all at the heart of good gaming architecture. One of the focus points of the article is the emergence of tools for users of games to create their own, and it only seemed logical that I should go through the process myself. In other words, I need to come up with a concept and try to develop and publish a simple game as if I were a student.

This post is the first bit of reflection on how that project is slowly developing.

My criteria for finding a good game creation platform was not all that scientific. I wanted something free (that could potentially translate into a no-cost project for my classroom), easy to use (this being relative, of course); and the ability to publish my game at some time in the future, if I wanted. The platform I decided upon, after some research, is GameMaker 8. I downloaded the software on Saturday morning and opened it up, with my older sons looking over my shoulder. They’re interested, too, particularly with the possibility of creating a game for their iPod (I need my Mac and a program called GameSalad – that’s for another day).

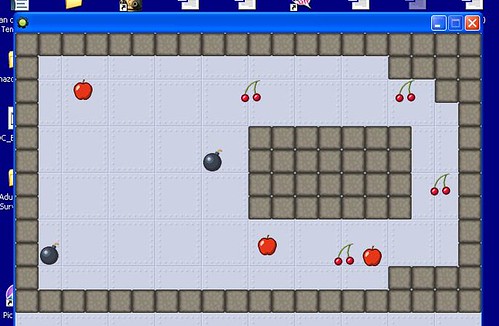

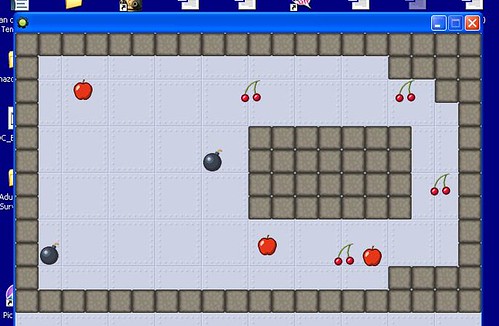

GameMaker 8 begins with a handy tutorial on making a simple game, involving moving fruit and the user collecting points by mouse clicking on the fruit (harder than it sounds). The tutorial was easy enough to follow, although the software is bit more complex than I thought it would be. I realized quickly that this is a whole new world for me, so the various elements and vocabulary that might be common in gaming systems for regular users are somewhat foreign to me. Still, the tutorial, with screenshots, was made for beginners like me. I made my simple game with bouncing fruit (and wondered, why fruit? When does fruit ever run away from us? I remember fruit being elements of some of the original video games that I played as a kid, too. Odd.)

At one point, I added a sound to the apples when they are clicked by the player – nothing fancy, just a little zing to indicate success — and my older son asked, “Why did you do that?” to which I answered, “Because I could,” and realized that I was echoing an answer often made by one of my students when they come across something cool. I kept the sound on the apple but realized I would have to try to be more thoughtful. A game that is overloaded with media and options is not very playable.

Ok, so I made my fruit game. What’s next?

What I really want to do is create a game with some sort of narrative backdrop. Again, one of the elements of my article is how “story” has infused a lot of the innovative gaming (Think of Spore, with its story of evolution, for example). I can’t get too complex because my knowledge of GameMaker is limited, and the software has limits, too (although an upgrade for $25 suggests more possibilities for game design).

So, here is my “story” of my future game: a student has woken up late, missed the bus, and must rush to get to school. Along the way, the student encounters obstacles, including a dog chasing them, nipping at their heels. The student gains speed by gathering things (what? I don’t know. Pencils, computer mice, erasers, etc.) along the way. So, this is a Maze Game, I realized, and I think it is doable for someone of my skills. I’m not all that certain the “story” will be evident, but it will at least guide me along as the developer.

Looking at the GameMaker site, I realized there are tutorials on creating maze games, so that is my next step. I’m going to spend some time with the tutorials and begin the task of making a basic maze game, with my own story concept lurking in the background. And I would probably benefit from drafting a paper version of the game, too, to help keep my focus. I also had this vision of writing a story of this running-late student (Running Late – possible name of game), with the game yet another element of the storytelling (and maybe a Google Search Story, too?) so that the story itself becomes multi-modal and engaging for the reader, who also becomes a player in the story.

Now, how would you pull all that off in the classroom?

Peace (in the sharing),

Kevin